01: Le Corbusier, Unité d’Habitation, Marseille (1952), Phaidon (ed.), Le Corbusier Le Grand, New York 2008; S. 422

Post-war modernism has long since been a major focus of historical research. Such interest justifies on-going efforts to preserve buildings of that period – despite being often at odds with the public’s contempt for this much-maligned style of architecture. A wealth of historical research into the modernist architecture of the 1950s is available already yet more recent historiography is making increasingly apparent the need for sustained inquiry also into subsequent developments within post-war modernism. The chronological parameters of this architectural epoch remain hazy, for instance, as do the underlying connections between post-war modernism and late modernism. It might also be argued that the crisis of late functionalism around 1970 and the subsequent postmodernist backlash were rooted in the closing years of post-war modernism.

02: Alison and Peter Smithson, Secondary Modern School, Hunstanton (1949-54), Alison and Peter Smithson, The Charged Void: Architecture, New York 2001; S. 56

03: S. 60, 04: S. 67

Brutalism is crucial to an understanding of transitions in this period. An outcome both of generational conflict at the CIAM (Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne) of the late 1940s, and of the subsequent work of Team 10 Brutalism (to quote Alison Smithson) signalled the appropriation and transformation of ‘heroic modernism’. Pursued in the 1950s and 60s as an international project – initially in Great Britain then in various national architectural contexts in the USA as well as in Japan – Brutalism by the late1960s and 70s had become an integrative element of the international shift towards urban density and away from the functional city and functional separation in the Corbusian sense. In fact, Brutalist aesthetics pervaded the subsequent crisis of late modernism even, and to no small degree.

05: Stadtplanungsamt Sheffield (J. Lewis Wormesley, Jack Lynn, Ivor Smith und Frederick Nicklin), Siedlung Park Hill, Sheffield (1961), Reyner Banham, Brutalismus in der Architektur, Stuttgart 1966, S. 183

Brutalism is a priori the diffuse project of a generation whose quasi, fundamentalist revival of an authentic aesthetic by recourse to the materials of modernism and the striking, no-frills look of béton brut was simultaneously a call for a code of ethics: a code with bearing on the everyday role played by the built environment in inhabitants’ lives – on everyday culture as opposed to high culture. This theoretical strand within Reyner Banham’s admittedly controversial codification seemed likely to breath new life into modernism’s original yet in the meantime, obscured motifs. However, this is only one among many possible readings of Brutalism’s impact.

06: Vittoriano Viganò, L’Istituto Marchiondi Spagliardi, Mailand (1959), Franz Graf, Letizia Tedeschi, L’Istituto Marchiondi Spagliardi di Vittoriano Viganò, Mendrisio; S. 191

07: S. 242, 08:S. 231, 09: S. 183

While intensive research has been devoted for some time to Team X (whose debates in the mid-1950s amounted virtually to a Brutalism think tank), little attention has been paid as yet to Brutalism in distinction, firstly, from post-war modernism and, secondly, from parallel emerging trends such as formalism, structuralism, pop architecture and utopian projections. The criteria and benchmarks by which the Brutalist legacy might be clearly evaluated are therefore not yet in place.

The renaissance of certain Brutalist motifs and theorems in recent contemporary architecture is by no means paralleled by public appreciation for the architectural ‘manifestos’ bequeathed us by this movement. Indeed, as the demolition of the Pimlico School and the planned demolition of the large housing estate, Robin Hood Gardens, both in London, clearly signalize, moves to preserve this architectural heritage are highly controversial. Likewise in Berlin, preservation of the legendary St Agnes Church – the epitome of the German Brutalist movement, designed in the 1960s by Werner Düttman, former Director of Public Works for the Berlin Senate – is currently fiercely contested. The repercussions of this far-reaching debate are already also rocking the foundations of 1970s architecture, such as the IBA houses designed by John Heyduk.

10: John Bancroft, Pimlico School, London (1967), Robert Maxwell, Neue englische Architektur, Stuttgart 1972; S. 142

Our position on this topic is that Brutalism’s critical review of classical modernism and post-war modernism gave rise to a unique laboratory situation, in which modern architectural trends still of relevance today were developed and tested for the very first time. But not only did Brutalism’s aesthetic and formal features set the course of future developments, as late minimalism attests; the ethical, which is to say socio-political subtexts of its ‘Everyday Architecture’ approach likewise exerted a lasting influence on architectural and urban planning discourse, as evinced by the Las Vegas- and Suburbia-oriented postmodernism of Venturi, Scott, Brown, for example, or by the Dirty Realism of the late 1980s, which fostered a new urban planning approach to urban sprawl. To investigate Brutalism in the light of the above can thus contribute significantly to understanding key architectural developments that occurred in the later years of postmodernism.

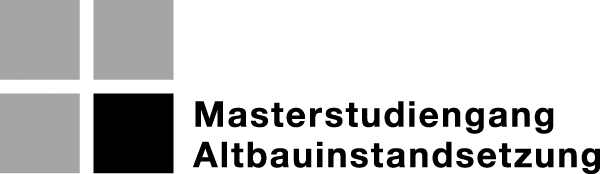

11: Werner Düttmann, St. Agnes Kirche, Berlin (1964-67), Haila Ochs, Werner Düttmann. Verliebt ins Bauen. Architekt für Berlin 1921 – 1983, Basel/Berlin/Boston 1990, S. 131, 12: S. 135

A crucial concern of the symposium is to establish substantial criteria and benchmarks, and thus promote the consistent and considered evaluation of the Brutalist legacy. We consider it imperative also to heighten public awareness and thereby foster a sensitive approach to this endangered architectural heritage.

13: Sergison & Bates Architects, Urban housing, Finsbury Park, London (2004-2008), Sergison & Bates Architects Prospect No. 05

In the light of papers presented by the discipline’s ‘Elder Statesmen’, the symposium will seek primarily to analyse architectural theory and the latest research into Brutalism as a theoretically underpinned architectural practice. A further ‘country-by-country’ strand will illustrate the histories of the major labs established by the Brutalist movement, and thereby reflect on their respective interactions. Both as a turning point and as a critical factor in late modernism, Brutalism paved its way out of its own era and into the present. New inter-pretations of Brutalism are not exactly a novelty on our horizons in the UK or Switzerland, for instance, and a growing appreciation of its discrete, understated impact is increasingly putting it back on the drawing board. The third strand of the symposium will therefore be to address contemporary manifestations of the Brutalist tradition, in the light of various areas of research and the open questions to which these give rise.